As coronavirus surges again, researchers find mortality rates are highest in rural counties

In parts of the country where COVID-19 is surging, residents of rural counties are dying from coronavirus at higher rates than those in urban areas, according to a new health policy brief by the University of Cincinnati.

Coronavirus infections are hitting rural parts of the United States previously spared, requiring a new approach to battling the pandemic, a multidisciplinary team of UC researchers said.

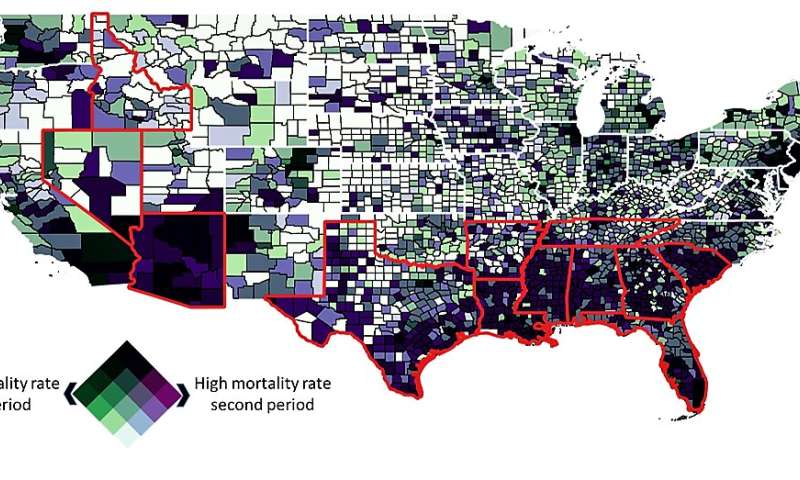

UC’s Geospatial Health Advising Group compared mortality rates from COVID-19 in the early part of the pandemic when some states were locked down to more recent months when most schools and businesses reopened. They also compared urban and rural counties in states with high and low rates of infection.

Composed of health, geography and statistical modeling experts from the UC College of Pharmacy and the UC College of Arts and Sciences, the UC group formed in the spring to track the virus and provide guidance for Ohio’s Department of Health.

Nationwide, urban areas have a higher rate of mortality from COVID-19 than rural areas. But in high-infection states where the virus is surging, the story is much different.

Rural concern

UC researchers warn that rural areas in these states have higher mortality rates from COVID-19 compared to cities. The epidemic shifted from the Northeast and mid-Atlantic regions to southern states that saw a surge in cases.

This is cause for concern for several reasons. Rural areas in the United States have fewer health care resources than cities. More than 16 million Americans live in counties with no surgical or intensive-care hospitals. And another 4.7 million Americans live in counties with no general medical or surgical beds at all.

The population in rural areas also skews much older than that of urban areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, which is a troubling consideration for a respiratory illness that is most dangerous to older patients.

Both factors make rural areas especially vulnerable to COVID-19.

“In mid-July hospitalizations were declining. Now they’re going back up,” said Diego Cuadros, assistant professor of geography. “It’s beginning to saturate the health care system, which is what we want to avoid.”

National recommendations

UC’s Geospatial Health Advising Group offered several recommendations:

- Urging government health agencies to recognize the disproportionate impact COVID-19 is having on rural areas when drafting county-level policies to address the pandemic.

- Making residents in rural areas aware of the risks they face so they can take personal measures to protect themselves.

- Improving health care resources in rural areas through health partnerships, particularly for critical access hospitals.

Some countries like Japan and South Korea have done a better job than others of employing contact tracing and preventive measures such as masks and social distancing to starve the virus of hosts. But it’s harder to isolate a virus in bigger countries with many points of entry.

There has been strong resistance in the United States and some European countries against lockdowns, social distancing and facemasks.

“We’re having the same national conversation now that we had in the spring,” Cuadros said. “People really want to go back to normal and it’s not happening anytime soon. It’s hard to convince people that they need to take precautions.”

UC College of Medicine student Dillon Froass condensed UC’s data, maps and pages of analysis to draft the brief as part of his fourth-year capstone project.

“I wanted to do something relating to the COVID-19 pandemic,” he said. “It’s been a great opportunity. You feel like you’re helping people. Policymakers can learn more from this so it will make a difference.”

Froass, a University Honors student and Darwin T. Turner scholar, plans to apply for medical school after taking a gap year to work at a hospital.

Froass said his college experience hasn’t been hampered much by recommended social distancing. UC has had comparatively few infections, suggesting students are taking the risk of infection seriously. To date: UC has seen 742 cases out of a student body of 46,388. UC set a new record for enrollment this fall.

Source: Read Full Article