False-Positive Lymph Nodes on PET Scans After COVID Vaccination

Editor’s note: Find the latest COVID-19 news and guidance in Medscape’s Coronavirus Resource Center.

Don’t be fooled by a false-positive lymph node after COVID-19 vaccination, say radiologists who report several cases, some of which led to unnecessary biopsies.

The COVID vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna (both of which are mRNA vaccines) can trigger reactive lymphadenopathy and radiotracer uptake on PET imaging, they report. This can lead to false positives, notes a team from the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

They report their findings in the American Journal of Roentgenology.

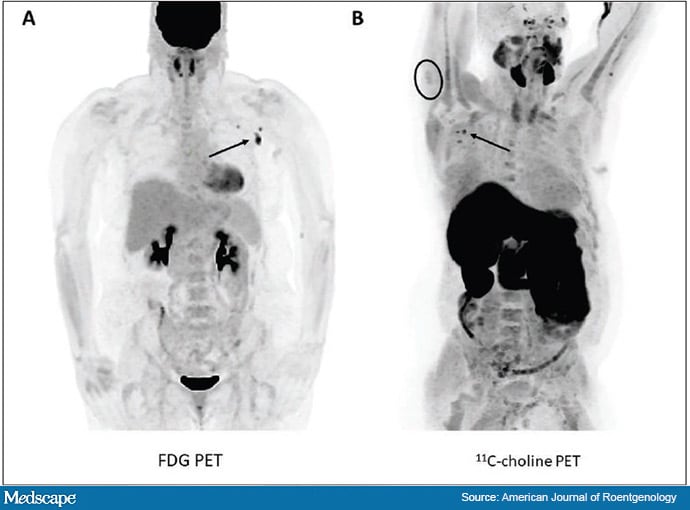

Seven of 67 cancer patients (10.4%) had axillary lymph node uptake of radiotracer on PET imaging within 24 days of vaccination, including four with uptake of (18F)-fluorodeoxyglucose) (FDG) and three with uptake of [11C]choline.

The positive nodes were on the same side as the vaccine shot in the five cases where injection site was known.

Maximum intensity projection PET images showing ipsilateral axillary lymph node uptake using two different radiotracers.

One patient also had FDG uptake in a supraclavicular node, also on the same side as his shot.

Four patients had received the Pfizer vaccine and three the Moderna injection. They previously had no uptake on PET scans.

“Radiologists should be aware that this can happen when they are interpreting PET imaging for both FDG and choline,” commented co-author Samuel Jang MD, a nuclear medicine and diagnostic radiology resident at the Mayo Clinic.

Screening for Vaccine History “A Must”

Three of the seven positive cases in the review also had uptake in their deltoid muscle as a result of inflammation at the injection site, so if ipsilateral deltoid and axilla uptake are found together, “it’s even more likely we can attribute it to COVID vaccination,” Jang told Medscape Medical News.

The 10.4% incidence of this uptake was lower than in previous studies, which have soared as high as one third of patients. The Mayo population was elderly, with a mean age of 76 years, so they might not have had as strong a reaction to the vaccines as the younger people included in earlier reports, the authors speculate.

Given the findings, the Mayo team said delaying PET imaging for 3-4 weeks after the vaccine might be reasonable.

Also, because the reaction seems to occur on the same side as the injection, others have suggested counseling patients to get the shot on the side opposite their tumor, if possible.

Clinicians at Mayo are now careful to screen patients about their COVID vaccination history and document it in the medical record system to help with image interpretation. Knowing on what side and when the shot was given “really helps,” Jang said.

Positive axillary nodes in the study had a mean short axis diameter of only 8 mm, and only one was abnormally enlarged. The lack of substantial enlargement might be another clue that a vaccine reaction is to blame, but other teams have reported a greater degree of lymphadenopathy.

The patient with supraclavicular uptake was also on immunotherapy with pembrolizumab (Keytruda), so it is possible he had an especially strong reaction to the vaccine, leading to uptake outside of the axilla, the team said.

The major limit of the study was that the positive nodes weren’t biopsied to rule out metastases or infection, but after careful review and considering previous negative PET scans, the team concluded they were most likely a result of vaccine reactions.

PET imaging was performed a median of 13 days after vaccination in the 44 patients who received one dose of vaccine and 10 days after vaccination in the 23 who received two doses.

The choline studies were for prostate cancer, and FDG imaging for other tumor types.

Increased FDG activity has been reported previously after other vaccines, but there seems to be an “even stronger association” with COVID-19 vaccination, the investigators noted.

No funding sources were reported, and the investigators have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AJR Am J Roentgenol. Published online May 19, 2021. Abstract

M. Alexander Otto is a physician assistant with a master’s degree in medical science, and an award-winning medical journalist who has worked for several major news outlets before joining Medscape, including McClatchy andBloomberg. Email: [email protected]

For more from Medscape Oncology, join us on Twitter and Facebook

Source: Read Full Article