iPhone Flash Helps Nurse Identify Her Infant Son’s Retinoblastoma

Josie Rock was taking pictures of her 3-month-old son Asher when the lighting in the room suddenly dimmed, initiating the flash on her iPhone. Asher’s eyes opened wide, but instead of his pupils glowing red, as they normally do when a flash is used, one of his pupils was white.

“His right eye glowed goldish-white, and his left eye was the regular red,” said Josie, a labor and delivery nurse who resides in Gainesville, Georgia. “I kept taking more pictures, and they were all the same.”

Josie pulled out a professional camera and attached a flash to make sure that what she was seeing was real and not just an artifact caused by the iPhone camera. The result was the same. The white glow was evident in all of the photos she took. A visit to Asher’s pediatrician a few weeks later and then one to a pediatric ophthalmologist confirmed her worst fears — her son had retinoblastoma.

Fortunately, Josie had learned about the “white glow” in a lecture only a few months before Asher was born. Juggling a growing family and nursing school is no easy feat, and she had been daydreaming in class during her pediatrics rotation. For some reason, she snapped to attention just as cancers were being discussed during a lecture.

“There were literally three sentences about retinoblastoma,” she said, “and then we went on to talk about something else. But for some reason, those three sentences stuck with me.”

When the ophthalmologist dilated Asher’s eyes, the tumor was visible. Asher was subsequently diagnosed with group D retinoblastoma. Thanks to the accidental flash of her iPhone camera and Josie’s awareness of the significance of what the photos showed, Asher was diagnosed when the disease was at a very early stage and was still relatively confined. The early diagnosis may have saved his life.

Although the tumor was large, it had not yet affected the optic nerve, explained his mother. “If we had waited longer, it could have metastasized.”

But even with an early diagnosis, it’s been a long haul for the Rock family. Asher required aggressive treatment, including systemic chemotherapy and laser therapy. “We even went to New York — to Memorial Sloan Kettering — so he could get intra-arterial chemotherapy, which wasn’t available locally at the time,” added Josie.

Asher is now 7 years old. He continues to be closely monitored, and although vision in the affected eye was lost, enucleation wasn’t necessary, and his eye is intact.

The Era of Smartphone Diagnosis

Smartphones, as the name implies, have uses that go way beyond making phone calls and sending text messages. Thousands of smartphone apps are commercially available, increasingly in the realm of healthcare. Apps are already being used as adjuncts to conventional approaches in such diverse areas as prenatal care, cancer, ophthalmology, and infectious disease to track, record, and connect data — and even guide many aspects of patient management.

In ophthalmology, apps have been developed that can test and monitor changes in vision related to macular degeneration or other distortions in the visual field, test visual acuity, and identify colors for people with color vision deficiencies. Imaging of the eye using smartphones has also become increasingly popular and allows for an inexpensive and mobile examination.

In Asher’s case, it was simply an unintended flash while taking an ordinary photo that enabled Josie to detect an aberration in her son’s eye.

As reported in the media, other parents have had similar experiences ― for example, a simple photo taken with a smartphone led to a cancer diagnosis.

Phoenix resident Andrea Temarantz was looking at photos of her 4-month-old boy when she noticed something odd — a white glow in the baby’s left eye. Cancer didn’t cross her mind. Like Josie Rock, she initially thought it was a problem with the camera. Then she got a new camera for Christmas, a Nikon D3300 DSLR, and the flash revealed the same glow she had seen in previous photos. She pointed it out to the pediatrician at the next visit, and her son was subsequently diagnosed with retinoblastoma.

“Flash snapshots, especially when the camera does not have the red-eye eliminator turned on, have detected leukocoria (“white pupil”) in children,” said Shizuo Mukai, MD, an associate professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. “Leukocoria is a sign of a variety of eye conditions, the most serious being retinoblastoma — a malignant cancer of the eye in children.”

Screening for Retinoblastoma

Retinoblastoma is a rare ocular malignancy of childhood. The global incidence is about 11 cases per million among children younger than 5 years. In the United States, an estimated 250 to 500 new cases occur annually.

“It can be difficult to pick up retinoblastoma; it can take months to grow, and it is highly variable,” explained Thomas Olson, MD, director of the Solid Tumor Program in the Aflac Cancer Center and professor of pediatrics at Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia. Olson is the oncologist who treated Asher Rock.

Olson pointed out that premature infants are routinely screened for retinopathy. “That’s clear-cut and regimented. And well babies are supposed to have an eye exam and basic screening, usually at ages 2 and 4 months. But that’s typically the only screening done for retinoblastoma,” he said.

Retinoblastoma is caused by a mutation in both copies of the RB1 gene in a retinoblast, which ultimately leads to tumor growth. Olson explained that there are two types of retinoblastoma. The nonhereditary type, or sporadic disease, is responsible for about 60% of cases and will typically develop in one eye. The RB1 mutation will usually not be passed to future generations.

The other 40% of cases result from the hereditary type, which can be familial or sporadic. In familial hereditary retinoblastoma, a parent, sibling, or other family member has a history of retinoblastoma. “The familiar form tends to get picked up earlier because the parents are knowledgeable about the disease and so the tumor tends to be smaller,” said Olson, “although that’s not always the case.”

He emphasized that parents should have their child’s eyes checked if there are any problems at all. “If you see anything wrong, such as lazy eye, or the eye turning out, or whatever, it’s probably worthwhile to tell the pediatrician and have an ophthalmologist look at it,” he said. “It can be the first sign of retinoblastoma.”

Once in a while, people take a photo of a child, see the white reflection, and realize something isn’t right. “It doesn’t happen that often, but in Asher’s case, it was very useful,” Olson noted. “Taking photos with a phone is so easy now, and of course people are going to take pictures of their kids.”

That said, Olson isn’t advocating that parents use iPhones to intentionally screen their children for retinoblastoma themselves.

Rocking the Cradle With an App

Bryan F. Shaw, PhD, a professor of chemistry at Baylor University, Waco, Texas, takes another view on this. His son, Noah, was diagnosed with retinoblastoma when he was 4 months old. Although Noah survived the disease, his eye could not be saved.

The diagnosis was made during an eye exam. Shaw noticed the pale reflection from the back of the eyeball, which suggested the presence of a tumor. He wondered if that same reflection was apparent in flash photos taken when his son was younger. His hunch was correct ― the “white glow” was noticeable in pictures that had been taken when Noah was just 12 days old.

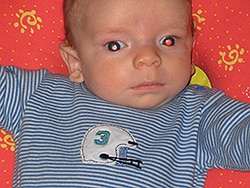

Noah Shaw, age 3 months. Courtesy of Bryan F. Shaw, PhD.

Both of Noah’s eyes were affected. “By then he was 4 months old, and we couldn’t save his right eye,” said Shaw. “If he had been diagnosed earlier, he would have needed less treatment in the right eye.”

Because retinoblastoma and other infant eye abnormalities are often first noticed in photographs, especially now with digital photography, which allows hundreds if not thousands of pictures to be taken easily, he decided to create software that could scan photos for the “white glow” and thus aid earlier detection.

But why the need for an app? Why not just use a camera?

“It’s simple,” Shaw explained. “Sometimes you get a gray pupil instead of a white one, and you have to blow the picture up. Or the baby’s eyes aren’t open far enough, or you have to keep taking photos to try to capture the pupils.

“Importantly,” he continued, “you may need to take a lot of photos before it shows up or is noticeable. If you take two photos, you may only catch it in one. We needed to come up with machine learning algorithms that can detect this white eye in photographs, and software that can be embedded into social networking accounts and smartphones.”

Shaw and his team, which included Mukai, ultimately developed an app for the smartphone called CRADLE (Computer Assisted Detector Lekocoria). “It uses artificial intelligence and computer learning to detect leukocoria in snapshops taken with the phone,” said Mukai. “It can screen all of the snapshots in your album every month, and in addition, it can be used live to screen for leukocoria. It is available for free on both iPhone and Android platforms.”

To test the app, they analyzed more than 50,000 pictures taken of 40 children by their parents before they enrolled in the study. The cohort included 20 children with retinoblastoma, Coats’ disease, cataract, amblyopia, or hyperopia and 20 control children. Their results showed that for 80% of children with eye disorders, the application detected leukocoria in photographs taken an average of 1.3 years before diagnosis.

When downloaded onto a smartphone or tablet, the app will scan through unsorted libraries and highlight any photographs that contain potential cases of leukocoria. It will scan automatically on Android devices, but requires activation before every use with the iPhone. When a photo of concern is detected, the app suggests that the child be taken to a doctor for examination.

Shaw noted that the app does not require connection to the internet, which protects the privacy of the user and others in their photos. It does not require images to be uploaded to a server, and it does not track user activities. The software is downloaded and scans directly on the device.

“Saying that you’re looking for cancer can be scary for parents, so I want to emphasize that this is useful to check for dozens of eye disorders that cause leukocoria,” he said. “Many don’t get detected until the child is old enough to read a Snellen chart.”

If eye disorders are detected early, then they can be treated earlier. “For instance, parents may be told that their child is delayed, but it’s due to vision,” Shaw said. “So then the child gets glasses and development improves because they can see.”

The app can be downloaded free from the Apple Store and Google Play under the name White Eye Detector. The technology is free of charge to all users.

Some Delays but Doing Well

As for Asher Rock, he continues to do well, although the aggressive treatment has taken somewhat of a toll. “He developed a heart murmur, and that needs to be followed closely,” said his mother. “He also has attention-deficit disorder and some learning disabilities, which isn’t surprising.”

Asher is also behind in sports and coordination. “He’s not a fast runner and lags a little on fine motor skills,” she said. She is concerned about the amount of anesthesia that Asher has been given, because he needed to be anesthetized for each of his 54 eye exams.

“But he’s very social and loves people, and he can talk the paint off the wall!” she added. “And he loves sports and to play and is just a happy child.”

For more news, follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Source: Read Full Article