Novel Dual CAR T cell immunotherapy holds promise for targeting the HIV reservoir

A recent study published in the journal Nature Medicine, led by researchers Todd Allen, Ph.D., a professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and group leader at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, and Jim Riley, Ph.D., a professor of Microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, describes a new Dual CAR T cell immunotherapy that can help fight HIV infection. The paper’s first authors are Colby Maldini, a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania and Daniel Claiborne, Ph.D., a research fellow at the Ragon Institute.

“This study highlights how relatively straightforward alterations to the way T cells are engineered can lead to dramatic changes in their potency and durability,” Riley said. “This finding has significant implications for using engineered T cells to fight both HIV and cancer.”

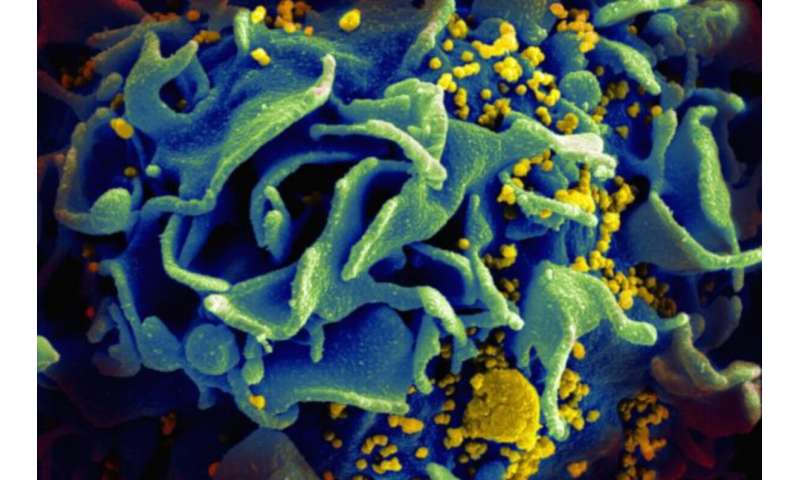

The global HIV epidemic impacts more than 35 million people around the world. Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is a daily treatment that can control, but not cure, HIV infection. However, access and lifelong adherence to a daily regimen is a significant barrier for many people living with HIV. A major hurdle to HIV cure is the viral reservoir, copies of HIV hidden away in the genome of infected cells. If ART treatment is stopped, the virus is able to rapidly make new copies of itself, ultimately leading to the development of AIDS.

CAR T cells are a powerful immunotherapy, currently used in cancer treatments, in which a patient’s own immune T cells are engineered to express Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs). These CARs re-program the T cells to recognize and eliminate specific diseased or infected cells, such as cancer cells or, potentially, HIV-infected cells.

Allen’s and Riley’s research groups worked together to design a new HIV-specific CAR T cell. They needed to design a CAR T cell that would be able to target and quickly eliminate HIV-infected cells, survive and reproduce once in the body, and resist infection by HIV itself, since HIV’s primary target is these very same T cells.

“By using a stepwise approach to solve each issue as it arose, we developed protected Dual CAR T cells, which provided a strong, long-lasting response against HIV-infection while being resistant to the virus itself,” Allen said.

This Dual CAR T cell, a new type of CAR T cell, was made by engineering two CARs into a single T cell. Each CAR had a CD4 protein that allowed it to target HIV-infected cells and a costimulatory domain, which signaled the CAR T cell to increase its immune functions. The first CAR contained the 4-1BB co-stimulatory domain, which stimulates cell proliferation and persistence, while the second has the CD28 co-stimulatory domain, which increases its ability to kill infected cells.

Since HIV frequently infects T cells, they also added in a protein called C34-CXCR4, developed in the lab of James Hoxie, MD, a professor of Hematology-Oncology at Penn. C34-CXCR4 prevents HIV from attaching to and then infecting the cell. The final CAR T cell was long-lived, replicated in response to HIV infection, killed infected cells effectively, and was partially resistant to HIV infection.

When the protected Dual CAR T cells were given to HIV-infected mice, the team saw slower HIV replication and fewer HIV infected cells than in untreated animals. They also saw reduced amounts of virus and preservation of CD4+ T cells, HIV’s preferred target, in the blood of these animals. In addition, when they combined Dual CAR T cells with ART in HIV-infected mice, the virus was suppressed faster, which led to a smaller viral reservoir than in mice who were only treated with ART.

Source: Read Full Article