Antipsychotics are increasingly being prescribed to children. Here’s why we should be concerned

An increasing number of young people in the U.K. are being referred to child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS). Alongside this is the rising number of children prescribed medicines that treat mental illness.

The evidence for the effectiveness and safety of these drugs comes almost entirely from studies in adults. Studies in children are rare.

While some of these drugs are effective in some children, the extent of improvement is often small. And there is limited information about the long-term safety in this age group.

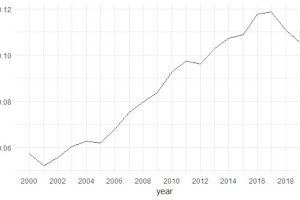

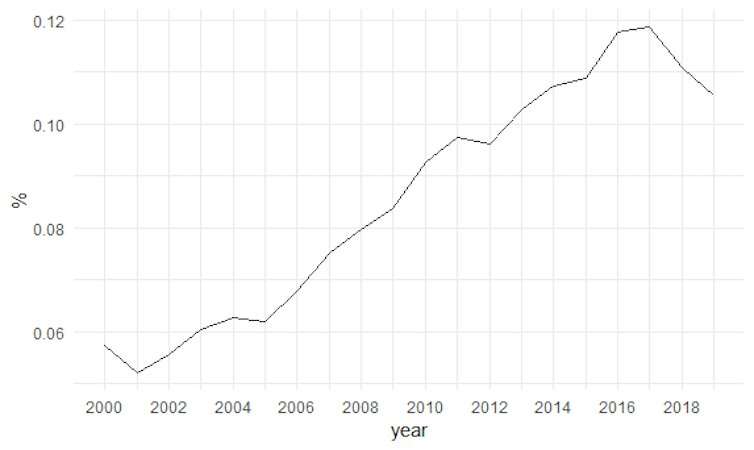

In a recent study, we report that the proportion of children prescribed antipsychotic drugs doubled between 2000 and 2019. We analyzed data from 7,216,791 people aged three to 18 years old.

In the U.K., antipsychotics, also known as “major tranquilizers,” are approved for use in under-18s with psychosis or with severely aggressive behavior. A growing body of evidence also suggests that two of these major tranquilizers, aripiprazole and risperidone, may be effective for improving irritability and “emotional dysregulation” in autistic children.

Although antipsychotics are most commonly being prescribed for children with autism and psychosis, they are also being prescribed for an increasingly wide range of other reasons, such as anxiety disorder, depression and ADHD.

In absolute terms, the overall percentage of children prescribed antipsychotics was small—0.06% of children in 2000 and 0.11% in 2019. Clearly, some children benefit from taking these drugs.

Yet increasing use of these drugs in young people whose bodies and brains are still growing and developing raises questions about safety. Evidence for this has yet to be established.

Antipsychotics have significant side-effects, including sexual dysfunction, rapid weight gain and a greater risk of type 2 diabetes, known as metabolic syndrome.

Antipsychotics are grouped according to whether they belong to the first or the second generation of drugs developed for psychosis treatment. The first generation was developed in the 1950s, but the drugs were associated with a risk of infertility, stiffness, Parkinson’s-like tremors and other involuntary movements.

Second-generation antipsychotics, first emerged in the 1980s and were initially thought not to have these effects. However, many do, such as the widely prescribed drug risperidone. In addition, they have been found to have other negative effects on metabolism, including rapid weight gain and obesity, diabetic-like changes to blood glucose, and pre-diabetes.

At the beginning of the period we studied (2000), we saw almost as many first-generation as second-generation prescriptions to children. After 2009, more than 90% of all prescriptions to children were second-generation antipsychotics.

But we also noted that the older, first-generation antipsychotics were more likely to be prescribed to children in poorer areas. The reason for this potential prescribing inequality is not clear, but it needs to be investigated.

Not everyone with a diagnosis needs a pill

The increasing number of children taking antipsychotics could, of course, be the result of more children needing these treatments and the potential benefits they deliver. But the fact that many more children are being referred to CAMHS does not necessarily mean that many more children need treatment with major tranquilizers.

Another possibility is that it reflects a reduction in the stigma surrounding mental illness or better awareness of mental health problems at an earlier stage of distress, and changing attitudes of parents, teachers and GPs about what CAMHS provides.

The number of young people experiencing anxiety and depression has increased, particularly in girls and young women, but there is limited evidence that the types of conditions requiring antipsychotic treatment are increasing.

A recent study reports that the number of children with a diagnosis of autism increased exponentially over 20 years from 1998, probably reflecting a growing awareness of the disorder. Yet most of these cases are children with milder autism—children who are unlikely to require antipsychotic drugs.

Increasing access to CAMHS can have a perverse influence on the quality of care, such that more young people receive readily available prescriptions rather than more resource-intensive psychological, social or family support. In such a landscape, health inequalities highlighted during the pandemic may increase, and in so doing, further disadvantage children and families least able to gain the help they need.

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Source: Read Full Article