Closer to cure: New imaging method tracks cancer treatment efficacy in preclinical studies

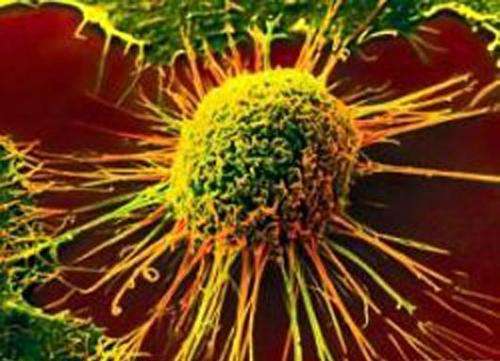

Several cancer tumors grow through immunosuppression; they manipulate biological systems in their microenvironments and signal to a specific set of immune cells—those that clear out aberrant cells—to stop acting. It is no wonder that immunotherapy designed to re-establish anti-tumor immunity is rapidly becoming the treatment of choice for these cancers.

One natural immunosuppressive molecule that helps cancer tumors is indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase 1 (henceforth, IDO1). Because it is found in a broad range of cancer tumors, including those of the skin, breast, colon, lungs, and blood, scientists have begun to see it as a promising therapeutic target: suppress its activity and anti-tumor immunity should return. But all endeavors so far have failed in phase 3 clinical trials—the stage at which a large number of people with the disease try out the optimal dose to test its true efficacy. Why is something so promising in theory and in the lab failing in late-phase clinical trials?

To find out, a team of researchers, led by Dr. Ming-Rong Zhang, Director of the Department of Advanced Nuclear Medicine Sciences at the National Institutes for Quantum and Radiological Science and Technology, Japan, tried positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to track IDO1 activity after a possible treatment has been administered. What they found is a breakthrough now published in BMJ’s Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer.

“In our paper, we highlight the development cycle of our PET imaging method, starting from tracer synthesis and biomarker identification to biomarker validation in a mouse model of melanoma treated with different immunotherapy regimens,” says Dr. Zhang.

The scientists began with a radiotracer—chemicals that emit radiation which can then be detected by machines—that is known to bind to IDO1. After establishing that this radiotracer can reliably reflect levels of IDO1 expression at specific sites in the body, they proceeded to find out whether it can also reflect the varied treatment outcomes of three combinatory immunotherapy strategies, each involving an IDO1 inhibitor.

They administered the radiotracer and the therapies to mice with a cancerous tumor and watched what happened over time through whole-body PET imaging. To their surprise, despite one of the treatment strategies clearly having greater efficacy than the others—wherein IDO1 was inhibited much more than in the others—the radiotracer uptake in the tumors seemed to be the same across all treatments. However, in the case of this standout treatment strategy, the radiotracer signal beamed in an off-tumor organ called the mesenteric lymph node. This was not the case for the other two treatment strategies. Further probing confirmed that in these lymph nodes as well, the radiotracer bound to IDO1. But why this organ? That is research for another study.

In this study, the scientists explored one more checkpoint: Did the peak and trough of this radiotracer in the lymph nodes mirror those of maximum tumor inhibition and decline of treatment effect? It turns out the radiotracer uptake increased from a few days before the peak, peaked with peak treatment efficacy, plateaued until a few days before treatment decline began, and fizzled out when the tumor relapsed.

So the scientists had stumbled upon an unprecedented new biomarker with which IDO1 activity could be monitored noninvasively, representing a promising alternative to invasive biopsy procedures.

Further explaining the results of the study, Dr. Lin Xie, co-author of the paper says, “Our findings imply that the IDO1 status in the mesenteric lymph node is an unprecedented surrogate marker of the cancer-immune set point, which is an equilibrium state from tumor tolerance to elimination, in response to immunotherapeutic intervention.”

Source: Read Full Article